3By: Shanita Li

Originally, ramen did not appeal to the general Japanese masses. Due to its difference from past Japanese food, there was dislike in the ingredients that made ramen. Ramen was greasy: using bones, pork fat, and meat, which was a stark contrast to the miso and shoyu the Japanese were used to in flavoring their own cuisine (Ayao, 2001). This was also in direct comparison to traditional style Japanese soups, which were typically made with dry and light ingredients (Han, 2010). There was also a large aversion to meat mainly because the Japanese diet largely consisted of seafood and vegetables at the time (Solt, 2010). With the late 17th century and the Meiji era, and the influence of more Western tastes did ramen start to take off in popularity.

However, it was with the defeat of the Japanese troops in World War II, that ramen underwent a significant change in meaning and perception. After the war, Japan was left in shambles with a severe food shortage which left the people in search of anything to eat (Han, 2010). Desperation drove people to eat insects, and plant roots to fend off starvation. All domestic planting and ceased due to destroyed farmland and infrastructure from the war (Ayao, 2001; Solt, 2010). All imports also ceased as Japan did not have the funds to buy food from Japanese or European colonies. Importing dropped to lower than 30% during 1943-1945, which is detrimental to a country which doesn’t have the soil and land to grow its own food (Solt, 2010). Rice imports from one of Japan’s greatest resources, Korea, dropped by 90% (Solt, 2010). In addition, whatever metal Japan had was given to war efforts, not agricultural production. After the end of WWII, it was hard for the country to recover.

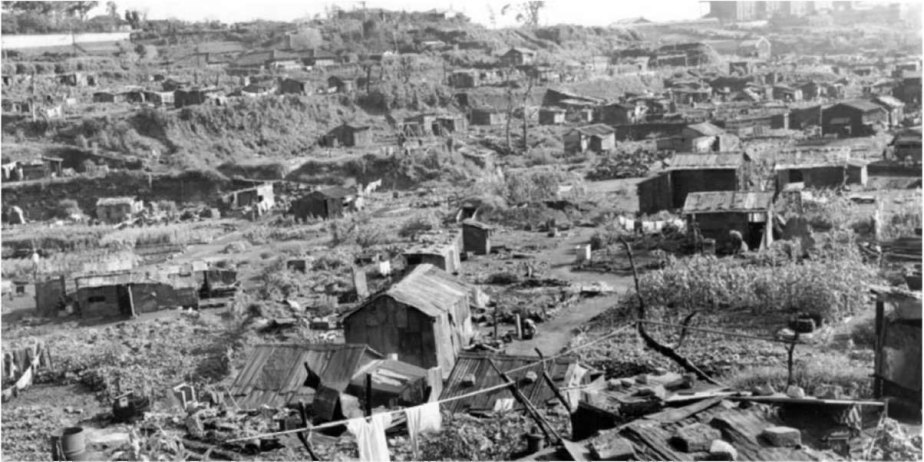

A shanty town that sprang up in Yokohama after fire bombings.

A shanty town that sprang up in Yokohama after fire bombings.

Black markets sprang up where neighborhoods were occupied by U.S. soldiers to steal food and other rations the Americans had. There was a scarcity of rice, and other staples such as sweet potatoes, soybeans, squash, and wheat flour which made up a good portion of the Japanese diet (Solt, 2010). The U.S. in agreement to help Japan recover, offered wheat flour at a discounted price to Japan to aid in recovery (Ayao, 2001). This propelled the popularity and necessity of ramen in Japan. Ramen played a key role in feeding the population as the noodles are made with wheat flour and substituted rice as a main meal. Food stalls that sold this Chinese-noodle style soup appeared all over Japan with hungry people waiting to eat what they called “stamina” food, a reflection of what the laborers and students referred to ramen before the war (Ayao, 2001; Solt, 2010). The dish was cheap and filling, able to provide high nutrient and calorie consumption in one bowl, making it ideal for the impoverished Japanese masses.

It was also due to the desperation for food, forcing the Japanese to eat food they would not commonly eat such as bugs and parts of vegetables once deemed inedible, that also shifted the perception of ramen in the public (Solt, 2010). Because eating ramen, as mentioned previously, was so different to what the Japanese were used to eating, it was avoided by the masses. However, war leads to the destruction of land which drives poverty making ramen an appealing option. The ramen made then was not the many variations commonly seen today. Rather, the soup base was filled with “floating shiny fat, strong odor of chicken bones, and the smell of alkali-water” which would be seemingly unappetizing to Japanese before, but was seen as a high energy food, which the Japanese wanted (Solt, 2010). To bolster the consumption of wheat and high-calorie food like meat, there were public relation campaigns that boast the superiority and benefits of wheat flour and animal-based protein which leads to an interest and perception of Chinese food as nutritious and filling (Solt, 2010). This all propelled ramen to its popularity within Japan leading to the creation of regional specialties and its status as a national dish.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources:

Ayao, Okumura. “Japan’s Ramen romance.” Japan Quarterly 48.3 (2001): 66-76.

Han, Kyung-Koo. “Noodle Odyssey: East Asia and Beyond.” Korea Journal 50.1 (2010): 60-84.

Solt, George. “Ramen and US Occupation Policy.” Japanese Foodways: Past and Present. Urbana: U of Illinois Press, 2010. 186-200.